Is it time to call time on pub closures in the UK? J Mark Dodds warns that we are losing more than our place at the bar.

Once the heart of community life, pubs are now disappearing at a rate that shows us something larger is at stake: the market itself is failing. In a country where people love a great pub, demand is obvious — yet instead of thriving pubs, we see shuttered doors and boarded windows. This is a catastrophic dysfunction, rooted in the extractive behaviour of pub companies draining profit while running pubs into the ground.

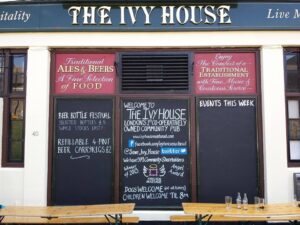

The loss is not just about drinking places, it is about losing civic space — the social infrastructure that sustains neighbourhoods, binds generations together, and provides a common stage for the everyday life of the nation. Pubs are safe and trusted places where communities gather, and bonds form across age, class, and background.

This is deeply personal to me. From 1995 to 2011, I ‘owned’ a tied lease at The Sun and Doves in Camberwell. It showed me how vital pubs can be for building communities, and how fragile they are when controlled by landlords whose only interest is extraction. Forced out by spiralling rents and profiteering beer supply prices, I carried that experience into years of campaigning for change in the tied pub sector. That same grassroots drive for action has recently led me onto CAMRA’s national executive, where I am determined to help reverse this social loss. (see box – My story)

But behind the scenes, I was in constant conflict with the pubco. Their model was — and still is — built on squeezing the business dry, extracting all the profit that came from my being an ‘exceptional operator’, wrecking pubs and communities in the process. This led to my co-founding the Fair Pint Campaign in 2008, and subsequently, I appeared before Parliament, providing evidence of pubco abuse to Select Committees. The Pubs Code came into effect in 2016 — the first real challenge to the beer tie. We changed the law, but it didn’t alter pubco behaviour or the rot of closures. Pubcos continue to aggressively churn publicans for profit as their pub estates collapse.

This came at a huge personal cost. A protracted rent review left me a back rent and costs bill of 150K; The Sun and Doves failed; I was evicted, bankrupted, and became homeless for 3 years. This story is but one of thousands of countless publicans forced into failure, their pubs run down, hollowed out, their communities left with boarded-up shells.

After that, I continued campaigning, unpaid, working with the British Pub Confederation and grassroots groups such as Licensees Supporting Licensees, Protect Pubs, and local communities trying to save their pubs. Out of that came the idea of a co-operative pub company —a structure that could protect pubs, provide them with the necessary framework, and secure community benefits.

By April 2025, as closures and brewery failures mounted, I stood for election to CAMRA’s national executive. I secured a four-year term because I believe CAMRA can reconnect with the lived reality of pubs and beer, and help lead a movement that reimagines the role of the Public House in 21st-century life.

The conclusion to this experience is obvious, if paradoxical: pubs succeed when they are made to serve people, not investors. The actual value of pubs — as safe spaces, trusted backdrops to community life, anchor points for everything else that follows — can’t be left to chance in a dysfunctional market that has failure built in. Success and stability must be built in. Growth must be sustainable; future success planned from the start. This demands a boardroom ethos where strategy serves the pubs, and the pubs serve their people. The paradox is that profits flow when the focus is not on EBITDA but on the business of people, on making communities stronger and lives richer. From this evidence comes the case for a National Trust for Pubs: a co-operative, funded by public subscription, that holds pubs in perpetuity and guarantees they are run for the common good. Scaled up, this is how the unique, yet vulnerable value of pubs can be secured — for communities now, and for the benefit of future generations in perpetuity.

The pressures on pubs are multiple, but the core issue is structural. Rents and tied prices have long tilted the odds against publicans. Energy costs and inflation have exacerbated the burden. Planning loopholes allow developers to cash in with ease. And the supposed “cultural shift” away from pubs is, in reality, the result of decline: as pubs were run down, stripped of quality beers, wines, and non-alcoholic options, and left unfit for purpose, people turned to home drinking. It was not people abandoning pubs — it was pubs being abandoned by the system that should have sustained them.

What is happening to pubs reflects something much deeper: the erosion of the commons.

The figures are stark. In 1980, there were about 70,000 pubs in Britain. Today, there are fewer than 40,000, and closures continue at a rate of more than seven a week. Every closure not only damages the economy but also extinguishes a vital meeting point —a hub of serendipity and community life that will likely never return. Like parks, libraries, and community centres, pubs are part of the everyday fabric where social trust is built. They are informal forums where people meet across divides, and in a society as fractured as ours, this role is more vital than ever.

Losing pubs means losing places where democracy is practised on a small scale: strangers become acquaintances, neighbours turn into friends, and issues are debated — sometimes resolved — over a shared table. To allow that space to deteriorate is to accept the further breakdown of civic life.

Yet out of crisis comes opportunity. The pub crisis has left us with thousands of boarded-up, neglected buildings — failed not because demand for pubs has vanished, but because decades of extractive ownership stripped them of investment, relevance, and the ability to serve their communities. Each of these closed pubs is not just a symbol of decline, but a foundation stone waiting to be reclaimed: raw material that can be turned back into thriving, contemporary community hubs.

The Spark of Opportunity

The wave of pub closures has galvanised a counter-movement: communities refusing to accept the loss of their local. According to the Plunkett Foundation, approximately 180 pubs are now successfully run by co-operatives, proving that ownership can shift from extraction to stewardship.

But the scale is nowhere near enough to stem the tide. Across the UK, dozens of pubs close every month, while only around 12–20 are saved by communities each year — roughly 15 annually, a figure that has remained consistent for over a decade. Over the same period, thousands of pubs have been lost. Plunkett has also reported that for every successful community buyout, many more attempts have failed — not due to a lack of will, but because the odds are stacked against them.

When a pub comes up for sale, locals often mobilise with passion and speed. But enthusiasm cannot substitute for capacity. Raising hundreds of thousands of pounds in a matter of weeks, usually through community share offers, is a monumental challenge. Banks rarely lend; the Community Ownership Fund was limited, bureaucratic, and has now been withdrawn. While Labour’s newly announced Community Right to Buy may help, it is too soon to know its impact. Owners — particularly pub companies — are often reluctant to sell to communities at all, since successful takeovers expose the myth that a pub was “unviable.”

Legal hurdles compound the problem. The Localism Act allows communities to nominate pubs as “Assets of Community Value,” giving them six months’ breathing space if a sale is triggered. But it is only a pause. Owners can still sell elsewhere, sometimes even at lower prices, to avoid the “problem” of community ownership. By the time volunteers have assembled lawyers, business plans and investment, the chance is often gone.

A People’s Pub movement could create a national capacity to change the game.

And even when acquisitions succeed, that is when the hard work begins. Running a pub is one of the most complex small businesses in Britain, involving long hours, licensing, HR, compliance, cash and stock management, food and drink service, marketing, and hospitality. It often takes two to three years to build resilience, and new businesses are most vulnerable in that period. Volunteers can quickly burn out, and a struggling pub can wipe out years of fundraising efforts.

That is why a People’s Pub movement — a National Trust for Pubs — could change the picture. Instead of each community starting from scratch, a regional or national organisation could pool finance, employ professional negotiators, and hold pubs in perpetuity. Local groups would still shape and run their pubs, but the risk would be spread across a portfolio, and professional support would be built in.

The effect would be speed and resilience. Communities would have agency without carrying the entire legal, financial and operational burden. If saving pubs is to become a national priority, this may be the only way to transition from saving dozens to thousands. Imagine one million people each contributing £10 to create a community-powered pub company. This company could purchase already existing pubs on the market, involve local communities in their revitalisation, manage refurbishments with local trades, and return them as vibrant hubs suited to 21st-century life. Investment could come via shares, tokens for future purchases, or subscription models. The pubs would be professionally run on behalf of their communities.

Crucially, this would be a commercial operation, not a charity. Each pub would retain its individuality, craft, and personal touch — but backed by a central hub that holds the skills, systems, and industry knowledge small businesses usually lack. From mentoring to stock control, management accounts to compliance, the hub would service and support the pubs, ensuring they are not just busy but profitable. This is the opposite of the conventional pubco model: instead of extraction from the ground up, expertise flows downward to help pubs thrive. By putting people first, the business of pubs becomes stronger — and with the proper procedures, measurement and data, that vitality is converted into financial success.

A Model for the Future

This is not utopian. The components already exist. John Lewis has demonstrated how large-scale employee ownership can strike a balance between profit and purpose. Platforms like Omaze or Raffle House show how small collective contributions can raise large sums. The challenge is to combine these approaches: to build a national co-operative vehicle that channels micro-investments into a professionally managed pipeline of pub acquisitions.

Each People’s Pub would operate as a genuine business, not a charity: managed sustainably, designed for community use, and trading profitably. Together, they could form a network of locally rooted, nationally connected assets — retrofitted to run on fossil-fuel-free energy, serving locally sourced food, and sustaining fair supply chains.

Every pint served in such a pub carries a dividend beyond its price. It reduces isolation, offers affordable venues for life events, provides training and apprenticeships, strengthens local economies, generates tax revenue, sustains independent breweries, preserves heritage, and creates a sense of place. Most of all, it gives people agency —the ability to say, “This is ours.”

We have established national institutions to preserve country houses, canals, and woodlands. Why not pubs?

The public benefits are measurable. Studies show that community pubs enhance wellbeing, reduce NHS costs associated with loneliness, and generate local economic multipliers. They are inclusive spaces: increasingly diverse, alcohol-moderate, capable of hosting everything from choirs to chess clubs, wakes to weddings, and providing amenities and services that are otherwise absent.

We have national institutions to preserve houses, canals and woodlands. Why not pubs? Few other secular social assets combine history, culture and social value so completely. Few are at such risk of being lost forever. A National Trust for Pubs would be more than an organisation — it would be a movement: a nationwide campaign fostering civic pride, collaboration and sustainability.

This is not nostalgia. It is renewal. It is a revival. It is re-imagining the public house for the 21st century: as much a community anchor as a place to drink; a space for conversation, creativity and connection. A revived pub sector, rooted in people, not private equity, could be one of Britain’s most hopeful stories.