Jia-Ren Tan charts how the Malaysian state has plundered the fruits of the labours of the country’s family farms.

In April 2025, state enforcement officers arrived in Raub—a highland town in central Malaysia’s Pahang state—armed with chainsaws. They felled over 1,000 mature Musang King durian trees despite a court injunction explicitly prohibiting their destruction. Protestor leaders, the Save Musang King Alliance chairman and local MP (see box – key figures behind the resistance), were arrested for “obstructing public servants in the discharge of their duties” when they tried to protect the orchards—both spent a night in police custody before being released on bail the following morning.

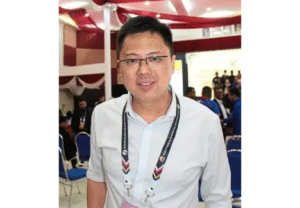

Educated at local schools and steeped in both agricultural knowledge and political strategy, Chang found himself thrust into leadership when the government announced its controversial “legalisation scheme.” His background as a former politician has been weaponised by opponents who claim the dispute is politically motivated rather than economic, but Chang’s coalition bridges ethnic and political divisions.

His evolution from local politician to agricultural strategist reflects the personal stakes involved; this isn’t just about policy for Chang, but about protecting his family’s livelihood and his community’s future.

As the elected MP for the area, Chow Yu Hui’s arrest alongside Chang during the April 2025 enforcement operation highlighted the political dimensions of the conflict.

The confrontation represents the latest escalation in a five-year battle over £18.75 million worth of durian trees across 8,000 acres and a fundamental question about who owns the value created by generations of farming knowledge in this former British colony.

Malaysia’s liquid gold

To understand this conflict, it helps to know that durians are Southeast Asia’s most polarising fruit. Banned from most hotels due to their overwhelming smell (imagine overripe cheese mixed with petrol), they’re beloved by food enthusiasts and command extraordinary prices. Musang King, a premium variety that only grows properly in Malaysia’s highland regions, such as Raub, can sell for £22.50 per fruit in Chinese luxury stores—more than most bottles of wine.

China imported £5.25 billion worth of durians in 2024, making it the world’s largest market

China imported £5.25 billion worth of durians in 2024, making it the world’s largest market for durians. This explosive demand transformed what was once subsistence farming into Malaysia’s agricultural equivalent of a gold rush, with Raub at its epicentre.

The story begins with Malaysia’s complex post-independence history. In the 1970s, as the young nation struggled with communist insurgency, government programmes encouraged rural families to settle and farm in strategic border areas, such as Raub. These settlers—many ethnic Chinese families who had fled to jungle fringes during the Emergency period—were promised eventual land titles in exchange for clearing forests and reporting on communist movements.

The variety itself was discovered when a local farmer brought a cutting from Gua Musang (a town in northern Malaysia) for grafting in the 1980s. What began as modest subsistence farming gradually transformed as global demand exploded.

The corporate takeover

This prosperity, however, came with a fatal vulnerability: most farmers lacked formal land titles despite repeatedly applying through official channels. It was only in 2020 that the Pahang state government announced a “legalisation scheme” that would finally resolve land ownership issues. Farmers could obtain proper titles, but only by signing exclusive supply contracts with Royal Pahang Durian Resources—a company chaired by the eldest daughter of Malaysia’s former King and current ruler of Pahang state.

However, the contract terms were deliberately punitive:

- farmers would sell their entire harvest to this single company at a fixed price of RM30 per kg (£5.63) for Grade A Musang King, which was at the lower end or below the market range of RM25-50 per kg (£4.69-9.38);

- a one-time payment of RM6,000 per acre (£1,125) for 2020; and

- production-based levies of up to RM20,000 per acre (£3,750).

Farmers also couldn’t form cooperatives, couldn’t sell to competing buyers, and couldn’t refuse without facing immediate eviction.

This represents a potent combination of royal privilege and state power unique to Malaysia’s political system

This represents a potent combination of royal privilege and state power unique to Malaysia’s political system, where constitutional monarchs retain significant economic influence despite democratic governance (see box – Malaysia’s unique political system).

Royal Pahang Durian Resources exemplifies how traditional monarchy intersects with modern capitalism. The company is chaired by Tengku Puteri Iman Afzan Al-Sultan Abdullah, the eldest daughter of the current Pahang ruler, who previously served as Malaysia’s King (2019-2024). This royal connection affords access to state resources and political protection that is unavailable to ordinary businesses.

Multi-ethnic resistance

In 2020, 204 farmers filed a class-action lawsuit challenging the arrangement. Their legal battle resulted in an initial victory when the Court of Appeal issued an injunction in May 2023, prohibiting the destruction of durian trees. But enforcement actions continued despite the court order—a pattern familiar from Malaysia’s authoritarian past when state power often overrode legal protections.

farmers united by a shared economic threat rather than ethnic identity

Understanding the alliance requires a grasp of Malaysia’s intricate ethnic dynamics. The country’s population is roughly 60% ethnic Malay (who enjoy constitutional privileges), 23% Chinese, and 7% Indian, with these communities often maintaining separate social and economic networks.

The Save Musang King Alliance represents something remarkable in this context: 80% Chinese, 15% Malay, and 5% Indian farmers united by a shared economic threat rather than ethnic identity. In a country where politics often divides along racial lines, this coalition conducts meetings in multiple languages and shares strategies across traditional ethnic boundaries.

A new threat

In May 2025, farmers faced an even greater challenge when DOA Plantations — a previously unknown company with unclear ownership — claimed ownership over 6,000 acres of durian orchards. The timing raised suspicions among legal observers that this new entity might be circumventing the ongoing court case.

Facing this new threat, the alliance chairman made a tactical decision familiar from Malaysia’s political playbook—strategic compromise with one opponent to focus resources on a greater threat. On May 28-29, 2025, the farmers began considering an out-of-court settlement with Royal Pahang Durian Resources while shifting their focus to challenge the mysterious new claimant.”

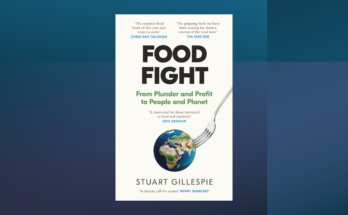

A global pattern

The battle for Musang King represents more than a local land dispute—it reflects a global pattern in which traditional farming communities face displacement as their crops become increasingly valuable internationally. Similar conflicts have emerged around premium coffee in Indonesia and speciality mangoes in Thailand as global markets discover Asian agricultural treasures.

The farmers ask to be treated as equal partners.

The alliance’s four demands reflect fundamental economic justice: collaboration as equal partners, free market pricing, reasonable land taxes, and shared environmental conservation costs. As the alliance chairman emphasised, “they do not wish to fight the government, but the unfair contracts are unacceptable. The farmers ask to be treated as equal partners.”

The resolution will determine whether Malaysia’s durian industry—targeting £375 million in exports by 2030—continues benefiting from multigenerational farming expertise or shifts toward industrialised plantation models that prioritise volume over the traditional quality standards that made Musang King globally coveted.